Legacy Matters

TREE’s work starts with the records of enslavement, but the story does not end there.

The documents we hold record people who were denied freedom, family, and identity. After emancipation, their descendants stayed in the Caribbean and built new lives within societies that were still shaped by British rule.

A century later, those same islands were part of the Commonwealth. When Britain faced labour shortages after the Second World War, people from across the Caribbean were invited to help rebuild the country.

Many of them were the great-grandchildren of the men and women whose names appear in the records now held by TREE.

For TREE, this is not a separate story. It is the continuation of the same journey. The movement from enslavement to emancipation to migration shows how endurance became contribution, and how identity moved from being recorded by others to being defined by the people.

By preserving both the early records and the modern voices, TREE connects the written archive with the living one. Together they form one history of survival, movement, and belonging.

Through these voices, the past is no longer silent, it speaks, reminding us that history is not finished, it is still being lived.

The Voices of Legacy recordings capture this living history. They are the words of those who lived through the years that followed Windrush and of the generations who inherited their experiences. These recordings sit alongside TREE’s artefacts as the sound of memory, identity, and truth in our own voices.

These recordings capture Desmond Johnston reflecting on his journey from Jamaica to Britain as part of the Windrush generation. In his own words, he recalls leaving home, adapting to a new country, and his hopes for what TREE will achieve in preserving these stories for future generations.

Being Left in Jamaica

Before joining his parents in Britain, Desmond spent years living with grandparents in Jamaica. Here, he reflects on what it felt like to be the child who stayed behind while others left.

The Day I Left Jamaica

Desmond remembers being just ten years old when he was told he was “going to see his parents” - not realising he was leaving Jamaica for good. His words capture both innocence and the heartbreak of separation.

School Life in the UK

Desmond recalls his early school days in Birmingham, the shock of the cold, and the challenge of finding acceptance in a country still learning to understand its new communities.

What Was Your National Identity?

Growing up in Britain, Desmond describes learning to balance two worlds - Jamaican roots and British life - and how he came to define himself as both.

What Do You Hope We Achieve at TREE?

In this reflection, Desmond shares his hopes for TREE - that preserving these stories will help future generations understand what the Windrush generation endured and achieved.

The following recordings represent the personal memories and views of Desmond Johnston. They are shared as part of TREE’s “Voices of Legacy” oral history series and do not necessarily reflect the views or positions of TREE as an organisation.

Migration trunk used by Beresford David Johnson, a member of the Windrush generation, when travelling from the Caribbean to Britain in 1955. The original green paint and red-pink lining remain, linking TREE’s eighteenth- and nineteenth-century archives to the mid-twentieth-century migration of Caribbean descendants to the UK.

Desmond Johnson, British Army, late 1960s After arriving in Britain as part of the Windrush generation, Desmond Johnston joined the British Army in 1968. He found belonging, discipline, and respect in a country that had not always welcomed him. His service reflected the loyalty and resilience of a generation who helped rebuild post-war Britain while still fighting for acceptance. “I joined the Army to get away - but it became part of who I was.”

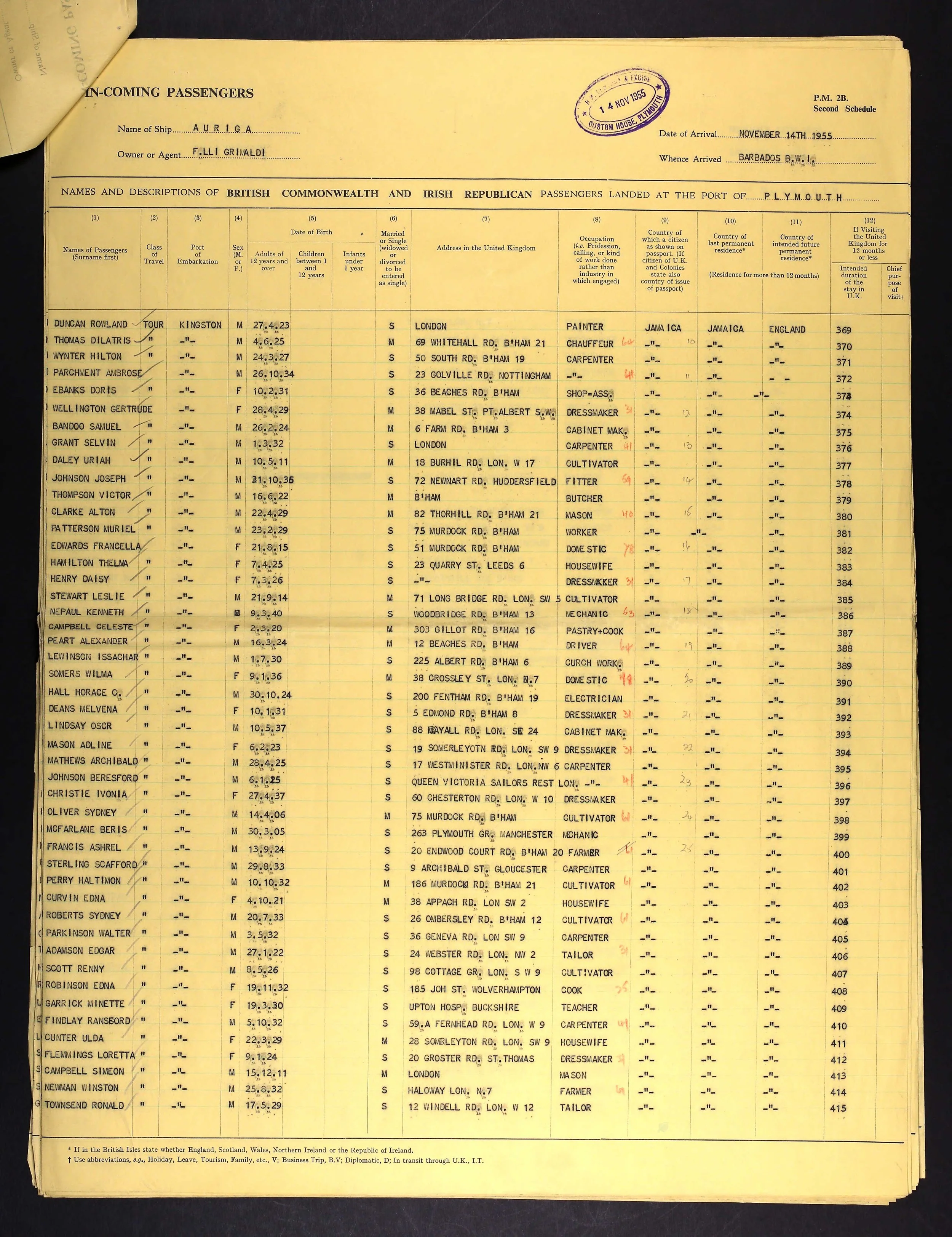

Passenger List, Auriga, 14 November 1955 The name “Beresford Johnson” appears on this passenger list from the Auriga, which arrived in Plymouth from Barbados in November 1955. Like thousands of others, he had been invited to Britain to help rebuild the nation’s workforce. These lists - once mere bureaucratic records - now stand as proof of courage, migration, and belonging. “A line on a passenger list became the start of a family’s British story.”

Beresford David Johnson, c.1954, Jamaica Before travelling to Britain in 1955 as part of the Windrush generation, Beresford Johnson worked as a skilled carpenter in Jamaica. This portrait was taken shortly before his departure. He would later spend his working life in Britain, contributing to post-war reconstruction and raising a family whose legacy continues through TREE.

Passenger List, Arosa Kulm, 27 December 1956 This official passenger manifest records Joyce Johnson (née Delahaye) arriving in Britain from Jamaica in December 1956. She travelled ahead of her young sons, Desmond and Dennis, as part of the Windrush-era migration. For families like the Johnsons, migration meant separation - mothers and fathers travelling first, children following years later. The documents that recorded their arrival are now part of the same national story as the ledgers that once recorded their ancestors’ enslavement. “Her name appears among hundreds - but each line is a life rebuilt.”

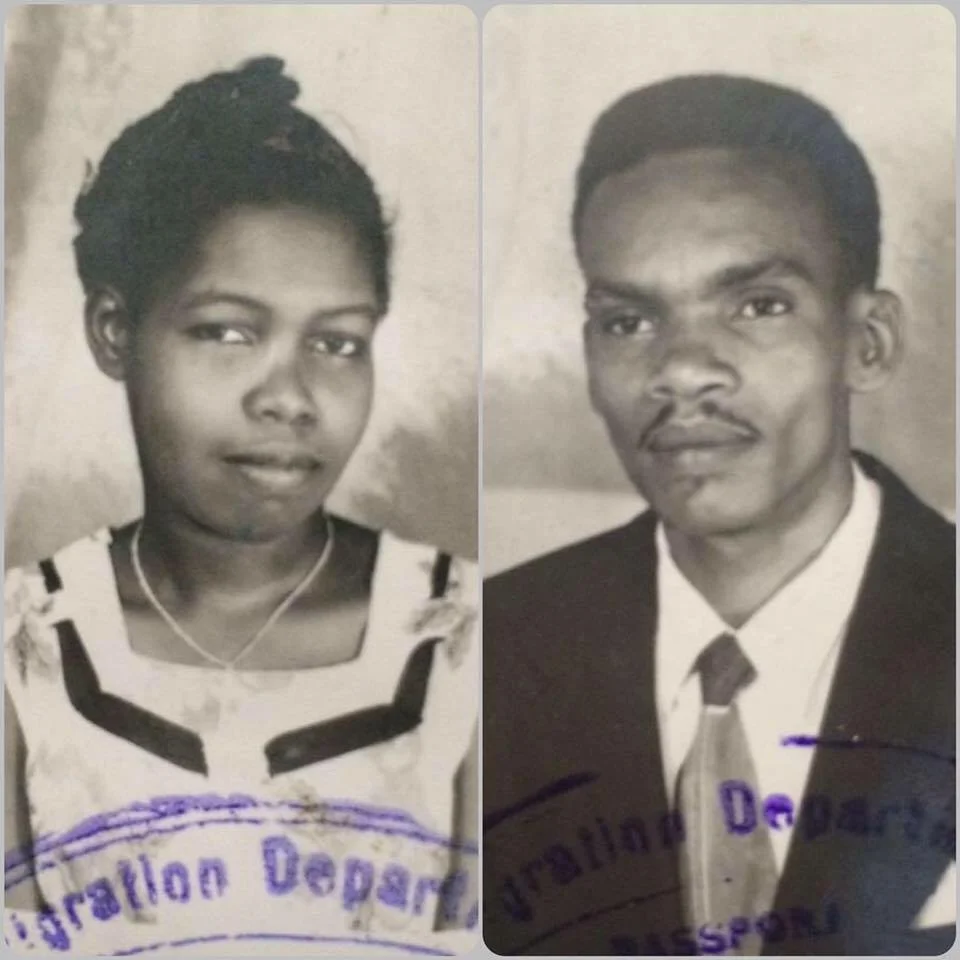

Joyce and Beresford Johnson, Jamaica, mid-1950s Photographed before their journey to Britain, Joyce and Beresford Johnson were among the thousands who left the Caribbean to help rebuild post-war Britain. Their migration marked the beginning of a new chapter for the family - one that would bridge continents, cultures, and generations.